The Day I Learned Why Government Can’t Work

In 1981, I learned a lesson that permanently changed how I understood incentives—and how they shape the way governments operate.

At the time, I was selling office equipment in Portland, Oregon, helping local businesses become more productive. I had built a reputation for introducing dictation systems that saved hours of clerical time. So when our company rolled out a new line of electronic typewriters, I was eager to show how they could revolutionize office work.

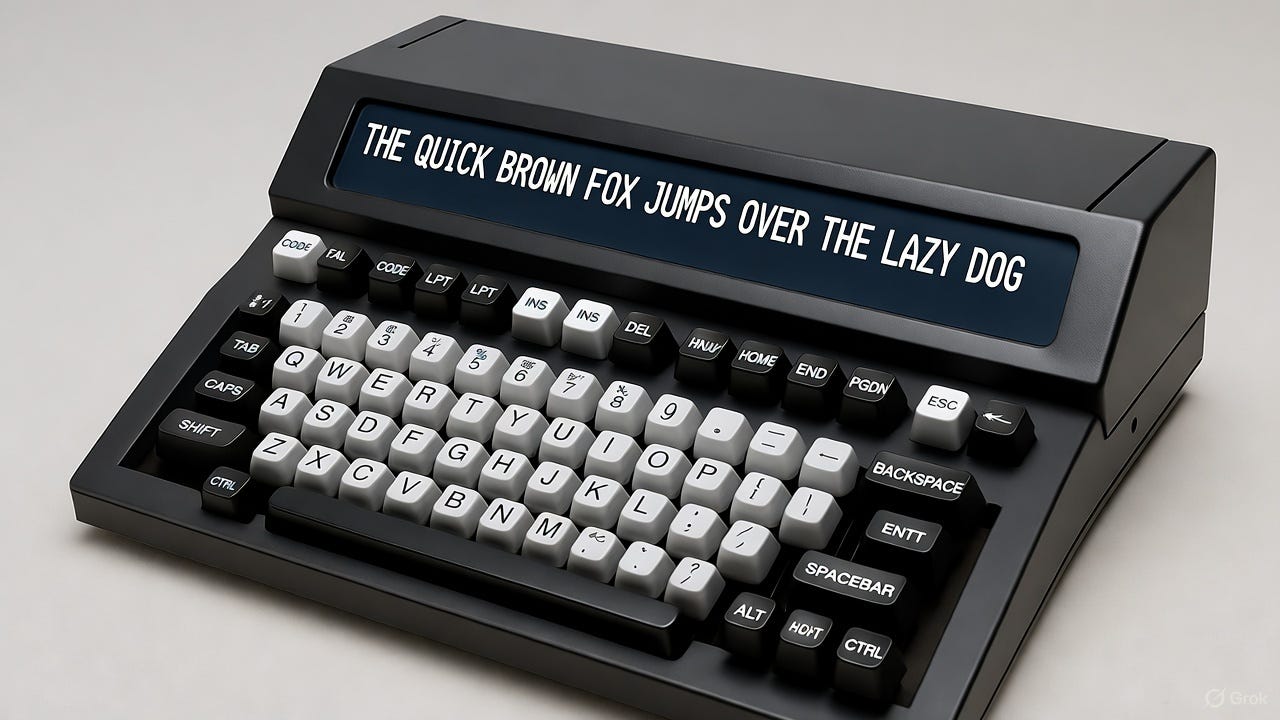

Back then, these machines were cutting-edge: sleek, humming marvels that could remember lines of text, correct mistakes automatically, and even store short documents in memory. The most advanced models cost around $3,500, a significant investment in 1981—but I believed the value they created would easily justify the price.

I wasn’t expecting my next sale to teach me something entirely different.

The Court That Didn’t Need Memory

One morning, I received an order—not a sales lead, but a purchase order—for five of the high-end typewriters from the District Court in Portland. The manufacturer had secured a government contract, so the sale was already made. My only task was to deliver the machines and train the secretaries to use them.

It seemed like an easy assignment—until I arrived.

To my surprise, these secretaries weren’t typing letters, reports, or documents that needed revision. Their sole task was to fill out government forms, each one different from the last. A typewriter with memory, capable of recalling text, was not just unnecessary—it was an obstacle. The older, simpler machines actually worked better for their job.

My challenge became disabling most of the “advanced” features just so they could use the new machines without frustration. I had to make the typewriters less efficient to make them usable.

Yet everyone was delighted with their shiny new toys.

Following the Money

The absurdity bothered me. Why had the court spent thousands of taxpayer dollars on equipment that didn’t fit their needs?

So, I asked questions.

What I discovered was a small but perfect microcosm of a systemic problem. The court’s budget for equipment had to be spent before the end of the fiscal year—or the remaining funds would disappear. Worse, their next year’s allocation would shrink.

Spending the money wasn’t optional—it was essential to survival.

The staff didn’t need better tools; the department needed to justify its existence. A smaller budget would signal less importance. If new equipment actually improved productivity, they might have to reduce staff—a further blow to status and influence.

I realized that bureaucratic incentives run in the opposite direction of entrepreneurial ones.

In business, efficiency earns rewards: you cut costs, increase value, and get promoted.

In government, efficiency is punished: you lose funding, authority, and sometimes even your job.

The Inescapable Incentive Trap

This single sale revealed more about governance than any economics textbook could have taught me.

People often complain about government waste, but few understand why it’s structural, not incidental. Every department, no matter how noble its mission, operates under perverse incentives. Success—measured as actually solving the problem the department exists to address—undermines its reason for continued funding.

Imagine a public agency that truly eliminates homelessness, or poverty, or crime. Its reward would be budget cuts and layoffs. Meanwhile, an agency that merely manages these problems, producing reports and pilot programs, can argue that it needs more money next year to “finish the job.”

The private sector works differently because feedback is immediate and measurable. A business that wastes resources goes bankrupt. A business that creates value earns profits, expands, and hires more people.

Government agencies, funded by taxes rather than voluntary exchange, face no such feedback loop. The link between cost and value is broken.

The Broader Lesson for Investors and Builders

That typewriter contract wasn’t an isolated story—it was a window into how entire systems can drift away from value creation. For entrepreneurs and investors, the takeaway is profound: when incentives misalign, even intelligent people make irrational choices.

This is why Free Cities matter. In a jurisdiction built on voluntary participation, budgets depend on satisfied residents, not on political optics. When people can choose their governance provider, efficiency and innovation become necessities—not risks.

If a city or developer wastes resources, people leave. If it delivers real value, people come. It’s that simple—and that powerful.

In retrospect, my 1981 experience wasn’t just about typewriters. It was about the human desire for security, status, and survival—and how the structure of governance channels those instincts.

In the marketplace, they produce progress.

In politics, they produce bureaucracy.

And that realization, sparked by a few overpowered typewriters in a Portland court office, became one of the most important lessons of my life.

Once upon a time, just after the discovery of electricity, my husband was a software programmer. He designed a multi-variable, multi-user database management system, which, in the pre-graphic interface days, still provided an easy to modify and use program for keeping track of and accessing information.

We had a handful of happy customers, who heard about it word of mouth. One example was an adult education nonprofit with 30,000 students and hundreds of courses; our system kept track of enrollment. Worked well.

We received a phone call from a state agency, which had an intriguing project. They were going to create a database of all of the active charities in the state and use it to build a calendar of events, so that the nonprofits would know what their colleagues were planning and, with practical keywords, to allow the general public to easily find information.

It would have been an easy-peasy job for us...except the very nice man told us that they had a $10,000 budget. After determining the size of the project and the deadlines, my husband and I decided that even though the job was within the scope of his software, it would be overkill for the relatively small number of records. We saw this as an opportunity to save the state some money.

As it happened, a new off-the-shelf program, which basically did what my husband's software did on a smaller scale, had been on the market for about a year or so, with stellar reviews–for less than $100. Easy to install, modify, and maintain. Also, a friend of ours–smart and trustworthy–knew the system inside and out and was available for consulting. And it was designed for small projects and had a very nice interface. They could be up and running in days.

So, when the state minion called back - a very nice man - we were eager to share the news. A great solution for him– excellent quality at a fraction of the cost. And, even if we had taken the job, it would have cost the state a couple of thousand at the very most, not $10,000.

And that was the start of an eye-opening conversation. The man explained that he was required to spend the $10,000 on the software project, even though we found him an option that was much cheaper, and, at the same time, better for the size of his project. Also I argued, it would better to work with a commercially available program rather than one produced by one person, which could be a problem if that one person was not available. But that did not matter, even though we could tell him where to buy it the same day, ready to install.

He explained that he was required to spend the entire $10,000 on this project, with no default to spend the excess on something else in his department or to transfer it to another department.

Why won't you take the money? he said, frustrated, confused, and increasingly anxious.

Because it would be unethical, I replied.

At the end, he went away to find someone who would take the contract. I am sure he did.

Not all of the government agencies I worked with had the same foolish guidelines. But, over 40+ years, I ended up turning down dozens of government contracts at the federal, state, and local level. By the way, I found the same attitude permeating large corporations and nonprofits. Assign a budget, and spend the money, regardless.

Essential. Thank you, Joyce.